- Published on

Home Server Security

- Authors

- Name

- Shiruvaaa

As you might have guessed, judging from where you are reading this from, you are probably aware that I have a personal home server. I run various services, including this blog-website and many others. Although it's super cool that I can host my own services, I will have to be on the lookout for potential dangers, such as possible exploits, DDOS attacks, vulnerabilities, things like XSS, remote access and flawed network security practices; there's just so much to keep in mind.

In this study, I want to find out how insecure my server is, why it would be in that state and how to solve potential dangers.

Is all this security really needed?

For a guy who self-hosts a couple of services from his own home, you could say that I don't have much to fear when it comes to getting hacked, but that might not be the case.

As I'm working in an "unprofessional" environment, I can't enjoy the perks of having business-level IT security. My home network, which I share with my family members, is a typical SOHO network. These kinds of networks consist of a couple of everyday devices, like laptops, smartphones, tablets, PCs, smart-TVs, etc. These devices are all eventually connected to one device: the router.

Business environments have a ton of security features, massive and often complicated infrastructures with big firewalls, but they still get hacked. Which begs the question: if those buffed-up networks get hacked, is my network and server safe? Probably not.

Still, what would an attacker possibly want to achieve by hacking me? They want the things from me as they want from any other average person on the World Wide Web: Information, which probably ultimately leads to money, amongst other things. If I want to mitigate the risk as much as possible, I'll have to use hacking methods on my own server to figure out my strengths and weaknesses. After all:

“To know what you know and what you do not know, that is true knowledge.” ~Confucius

Analysis

Where would you begin your search? The safest thing to try first would be to check on common practices.

Common practices are the things an owner of a server or network would normally do when maintaining a system. Think about regular (security) updates, checking on non-default passwords and more.

What are the best security implementations anyone can easily use?

Security updates. The most basic and simple thing, which is also highly effective for multiple reasons. Security updates are there to fix vulnerabilities for your installed services, applications and operating system. As people are always trying to take advantage of newly discovered bugs and vulnerabilities, it is best practice to install security updates as fast as possible. My services run on Ubuntu and software is thus updated by the package manager. Using prior knowledge, I have configured my server to install security updates automatically, which saves me a lot of trouble.

The package unattended-upgrades, which is installed on Ubuntu in most cases, is used for scenarios like these. To configure it to enable automatic updates for all the security patches in the system, we simply need to run the following:

sudo dpkg-reconfigure --priority=low unattended-upgrades

This command should write 2 different configuration files which are used to further configure the unattended upgrades. The gif below shows how to check if the installed config works as it should. This is an example of what would happen if the server executed the script. Notice the "no packages were found" at the end. (Sorry if you're looking at the gif in light-mode...)

But I shouldn't end it here. Now my OS updates all my packages whenever there is a new security patch out there. Sadly enough, those updates don't take my Docker containers into account.

Docker is mainly a software development platform and kind of a virtualization technology that makes it easy for us to develop and deploy apps inside of neatly packaged virtual containerized environments. Meaning, applications run the same, no matter where they are or what machine is they are running on.

Read more on what Docker is here: Docker in 2 minutes

Containers with their images are not always updated as they should be. The maintainer of the image could not always be up to date with updating their packages and releasing a new image. It's an occurrence I only recently began to think about but can be fatal if underestimated. I must keep in mind to check the reliability and activity of the owner of the application/image; see how much they update and release their software. Use trustworthy sources. Go for the direct owner of the software or use other trusted sources like Linuxserver.io, which I use for certain projects.

Be that as it may, using trusted sources is useless when you don't maintain your containers. My containers need to be updated whenever there's an update for an image. As containers don't store updates, the way to update one is to destroy the container and redeploy it with a newer version of the image. To automate this process, I use Watchtower. This is a more common method in the Docker world that monitors currently used images and installs them whenever a new one appears. The containers can then automatically be redeployed by Watchtower. There are other update alternatives and methods, but as Watchtower is a commonly used application, I'll keep it as it is.

Another simple one is passwords. Quite straightforward, but it should do the trick. Using a longer/more advanced password instead of a default password provided by a system should be common practice. Even if there's no default password given, say for an OS, it is good practice to use advanced and complicated passwords to mitigate the risk of a breach, especially with the lack of other security features, such as 2FA.

Personally, I make use of services like Bitwarden as a password manager. Passwords are mixed with numbers, symbols and upper/lower case letters and consist of at least 20 characters. Already a lot safer, right?

SSH

SSH itself is a secure protocol. Most problems occur with bad habits from the user. Let's examine these bad habits to see if I'm guilty of those.

First up is user management. There are cases where people have a Linux environment without extra users, meaning they only have root access and execute everything from the root user. Not very safe. An easy fix is to add a separate user. More and more Linux distro's come with an option to add an extra user with the installation, but you can always add one yourself using:

useradd shiruvaaa -m -s /bin/bash -c "user with admin privilege"

The __-c** is used as a comment.

Then, add the user to any admin roots so the created user can execute commands with root privileges (don't worry, the user will need a root-password for that).

usermod -aG sudo,adm,docker shiruvaaa

Notice that I add the user to 3 groups. \_sudo_ for sudo commands, _adm_ for reading specific log files and _docker_ so the user doesn't need __sudo__ to execute docker commands.

Lastly, the newly created user needs a password as well (for login and executing sudo commands). Simply execute:

passwd shiruvaaa

Most people – including me – would keep it at this. What I have failed to recognize however is the convenience and power of SSH-certificates. By using SSH-certificates, you can get rid of password authentication. The downside of passwords is remembering strong, long password strings and using them multiple times, which can not only be a hassle, but less secure than a certificate. Let's try and make one for my server!

I want to connect to my Linux server from my Windows machine using SSH, so that's where we start creating our SSH key pairs. We can generate a public and private key using the following command:

ssh keygen -b 4096 -C "silverfs-from-arvi"

The keys can furthermore be protected with an additional password. This is done to ensure the protection of the files key files themselves. As I have user authentication and encrypted storage on my machine, so I chose to skip this step.

Going into the folder .ssh, we get to see 2 new files among others, namely id_rsa and id_rsa.pub. The file without the .pub extension is the private key and should never be shared with anyone. This is equivalent to root access. The public key however can be used to share with any device, like my server, where the private key on my Windows machine is then used as an authentication for all the machines where I have distributed my private key to.

To use our key files, the server needs to have a copy of our public key. Using the command:

scp .\id_rsa.pub silverfs@silverserver:/home/silverfs/.ssh/authorized_keys

I copied it to a file in a new folder I made in my home directory. To permit the user to use the ssh key file, we'll need to add some permissions.

chown -R silverfs:silverfs .ssh

After this, we can check to see if we can login on the server without a password!

It works! But we're not completely done yet. We can now configure our server to only accept connections using a private and public key file. This further enhances the security access of my server. Execute the following line:

sudo nano /etc/ssh/sshd_config

And change the following entries in the file:

from:PermitRootLogin yes

to:PermitRootLogin no

and from:PasswordAuthentication yes

to no.

These options are self-explanatory. Restart your ssh-server using sudo systemctl restart ssh and you're done.

Network Security

There are a lot more security enhancements we can do with SSH and I have more security implemented at this moment, like Fail2Ban.

One Thing I also hear around the internet is the SSH port. The standard SSH port is 22. For seasoned hackers and cybercriminals, this port is one of the basic ports to check if it is in use on a system. Many people thus suggest changing this port to a different one. Despite that, everyone is in a different situation. Me personally don't see the value in changing my SSH port. I don't use SSH from the outside and as we just managed to login with a certificate, not including other security measures I use, it seems kind of pointless to change it. And, if a hacker really wanted to get SSH access, they would simply perform a port scan. And that's where network security comes in.

Firewall Enabling the firewall on your Linux server ensures that you have exact control on what ports you use for traffic. Knowing what you use and what you don't further improves the network flow and security of your server.

I use UFW - the Uncomplicated Firewall. It is the default firewall configuration tool for Ubuntu and works like a charm. I make sure to open up only what's absolutely necessary. To decrease the number of open ports, I use a reverse proxy manager for my docker services. More on this later.

Network Segregation I have my server placed on the same subnet as all my other devices. It is necessary to be on the same subnet as other devices to be able to use a Pihole on my network. I could run a seperate Pihole instance on this network and migrate my server to a DMZ location configured from my router, but I don't have the resources for that. To alleviate the chances of a server breach on my main network, I concluded that it is for the best if I use a guest-WiFi network. Giving guests access to only the guest network will greatly reduce the chances of contact server hacks as it is its own separate network. It is not only the user that I can be skeptic about, but it's also the devices that they use and carry with them. If a guest comes over with an infected laptop and connects to my main network, there's a bigger chance that something awful might happen.

Reverse Proxy Manager To close down unnecessary services on my router, I make use of Nginx Proxy Manager, which is a reverse proxy manager made to expose my services easier and more secure. Good job me!

A reverse proxy is a web server that sits in front of my application and it forwards client requests to them. Let's say I want to run an NGINX web server container which runs on port 3000. As this container doesn't come with an HTTPS server, I use my NGINX proxy manager to expose the server with trusted SSL certificates.

This also means that I don't have to open up a port on my router for every service that I use. The only two ports I need are 80 and 443, which are for HTTP and HTTPS respectively.

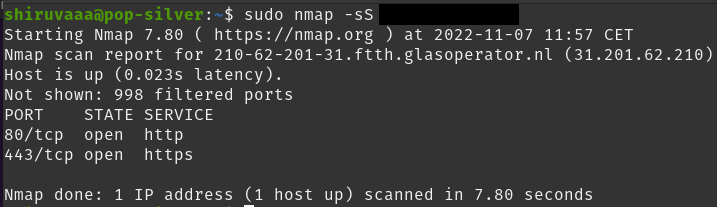

Stealth Nmap scans on my public-IP result in only two ports showing up. So, even if my public IP gets known, it will not result in much.

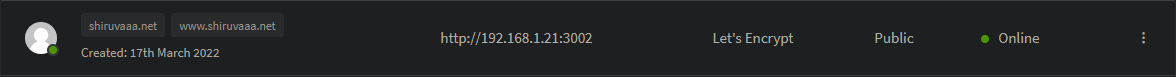

A Proxy Host is the incoming endpoint for a web service that you want to forward. Proxy Hosts are the most common use for the Nginx Proxy Manager. This is an example of my web-portfolio:

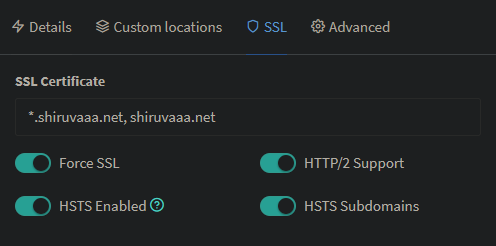

A proxy host, here shiruvaaa.net is forwarded to http://192.168.1.21:3002. Adding an SSL certificate is really easy. It provides support for a lot of domain name registrars and even free certificate creations with Let's Encrypt.

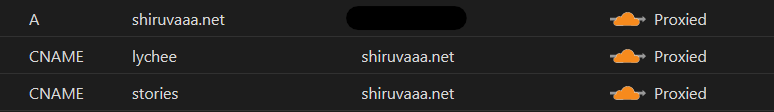

Even more security is added as all my services run through Cloudflare. Proxying my domain and subdomains through Cloudflare hides my own IP address. It also adds an extra SSL certificate provided by Cloudflare, which you can configure to create an end-to-end encryption for your services. It also supports DDOS protection and many more services.

What to do when an attack comes through?

Server security is never 100% guaranteed. So, when something somehow goes wrong and something comes through and exploits our web server, what do we do about it? And how do we minimize the potential damage?

One thing to try is to isolate the application. Limiting what app could do on the system greatly reduces negative effects of possible exploits and infections. Effective methods are things like AppArmor and containerizing applications, like Docker.

AppArmor is an effective application security system which proactively protects the operating system and applications from external or internal threats. It is by default installed and loaded on Ubuntu. Using the command:

sudo apparmor_status

It is possible to see which profiles are currently running on the applications. AppArmor runs a profile for every application to determine what permissions and files the application requires.

Another widely known way of isolating applications is by using Docker. Docker, as read earlier on, isolates applications in their own contained environment. The one thing that I have my doubts on is the Docker Socket, or the docker.sock.

Security-Enhanced Linux - Wikipedia

Taken from a Reddit posts backed by official documentation:

docker.sockis the UNIX socket that Docker daemon is listening to. It's the main entry point for Docker API. It also can be TCP socket but by default for security reasons Docker defaults to use UNIX socket.

Docker cli client uses this socket to execute docker commands by default. You can override these settings as well.

There might be different reasons why you may need to mount Docker socket inside a container. Like launching new containers from within another container. Or for auto service discovery and Logging purposes. This increases attack surface so you should be careful if you mount docker socket inside a container there are trusted codes running inside that container otherwise you can simply compromise your host that is running docker daemon, since Docker by default launches all containers as root.

Docker socket has a docker group in most installation so users within that group can run docker commands against docker socket without root permission but actual docker containers still get root permission since docker daemon runs as root effectively (it needs root permission to access namespace and cgroups).

More info at: https://docs.docker.com/engine/reference/commandline/dockerd/#examples

In the past, I've have created an alternative to Portainer, a popular Docker container management system. This alternative made use of the Docker Engine API through the TCP socket. This will lead to a decrease in security as anyone who has access to that port has full access to the Docker Engine.

Portainer makes use of the Docker socket where a unix domain socket (or IPC socket) is created at /var/run/docker.sock. This does not open up the socket port or any other way to access it remotely. It seems safer, but I still think there's a problem with it.

Since Docker by default launches all containers as root, there can be some serious security concerns when you use a non-trusted container. If there's no trusted code running inside the container, there will be no guarantee that the host can be compromised through the container with a socket connection.

It's a difficult subject, as root access might impact the host negatively, but despite that is still needed to create a relatively safe containerized environment. In theory, it cannot access the host's filesystem because of name spacing and cgroups from docker and as root inside the container is different than root on the host, you could say that it is a fairly safe environment. Nonetheless, anything can happen.

Podman

Podman is really similar to Docker. Podman too can launch containers with images, uses features like docker-compose as "podman-compose" and many other things like volume mapping, networks, etc.

Podman is rootless, which means you can run it as an unprivileged user without needing special system privileges and it's daemon-less, which means there's no stateful process that needs to continue to run on your machine. This makes it, seen not only from an infrastructure perspective but also from a security perspective very different. Podman being rootless is a security benefit as it allows you to isolate your users a lot more. When your user has access to Docker, it essentially has access to the entire machine, made possible by /var/run/docker.sock.

Because the way how Docker works, you interact with dockerd to spawn containers and communicate through the API. The API runs through a special socket-file, which is owned by root and the docker group.

You can add a user to the docker group to access the docker.sock which basically allows you to escalate to root via the socket. Scary.

I've used Podman back in the day but switched back to Docker as it didn't fit my needs at that time. Times are different now and Podman too has underwent a lot of updates as well so I would like to try it out and eventually switch back to using it.

Legal Issues

Earlier in this blog, I did some port-scans from the in- and outside of my network. Port-scans are fairly moderate in innocense but can still be seen as harmful – And I'm not talking about my own server.

What does my ISP think about all this? Does a responsible disclosure policy exist for this case? I've spent some time reading in my ISPs privacy policy and terms of service but found nothing of the sort. Asking a bit more around at my school grounds and adding my own thoughts, I came to the conclusion that **you shouldn't need to worry about pentesting your own network. Although many people might think differently, in itself, hacking is not a crime.

As long as you pentest your own network and don't do anything that is directly illegal, it should be safe to do.

You would have to be conscious of how the provider of wherever you stage your attack host sees this type of traffic.

Choice of staging location depends on what you're looking to pentest. If you wanna pretend to see what an outside attacker would see, scan the external IP; if you wanna see what vulnerabilities exist locally, only test from within the LAN, etc.

All that being said, unless you're hosting some services out on the internet for some reason, I would recommend doing everything locally.

Written from a Dutch perspective under Dutch and European law.**

Conclusion

Nothing is 100% safe and secure. There are countless methods and strategies to better secure your home server and one is better than the other. Things might get outdated quickly so don't take this post as a direct guide to server-security perfection. Try to do your own research as well!

I learned a lot by reviewing the state of my own server in this way and am proud to say that my research has paid off for me. It has made me think about certain scenarios and topics I wouldn't have thought about otherwise. It was refreshing to create an overview of my own server like this and whatever security methods you would like to implement, I would like to advice you to try this kind of approach as well.

Sources

Sources that helped me write this document.

- 10 Basic Information Security Practices

- How to get IPs/hostname from clients from different network(s)?

- Security - Firewall | Ubuntu

- dockerd

- Can anyone explain docker.sock

- FHICT Beleidswiki - Research:FHICT Beleidswiki

- Understanding root inside and outside a container

- Will pen testing my own LAN violate ISP rules?